By Eric Sandweiss

Charles Cushman has gotten me into some pretty tight spots. He’s dragged me through green pastures and led me beside still alleys. He’s drawn me closer than I cared to come to the shadow of death, as I weaved my car through freeway traffic with one eye on the road and the other on my map, one hand balancing a camera and the other tending to the steering wheel.

I didn’t know, when I started getting into those spots eight years ago, that I’d be following Cushman. As a historian of the built environment, I was after something else: the landscape of farms, small towns, and big cities that this part-time businessman photographed during the period from 1938 to 1969. I wanted to find the places Cushman had pictured, to learn how they’d weathered the transformations that had taken Americans from Depression, through war, and into a period of abundance.

I couldn’t help imagining that during that thirty-year interval, the nation had turned from gray to color. At least that’s how it had always seemed to a kid comparing the newest issue of Life, lying on the kitchen table (“Fonda’s Little Girl Jane as a Futuristic Space Traveler in the Movie ‘Barbarella’!”), with the clothbound early volumes of the same publication (“US Wins Race with Nazis for Brazilian Trade”) that he would pull off the shelves at the public library on a rainy Saturday afternoon.

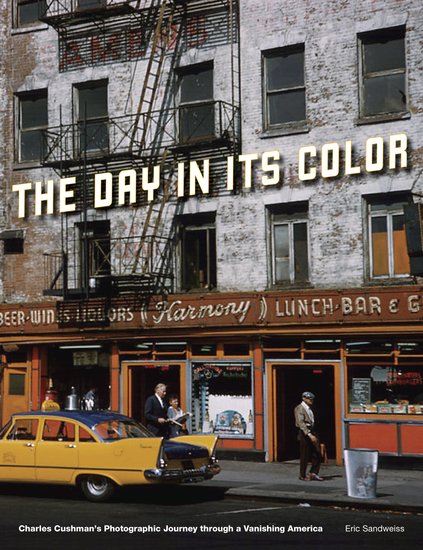

It was many years after those library weekends that I found Cushman’s pictures. I was old enough to know better, but somewhere beneath the superficial layers of graduate-school polish, the rough formulas had stayed with me. Old World: Gray. New World: Color. So when Indiana University archivist Brad Cook showed me the collection of fourteen thousand Kodachrome slides that he and his colleagues had just digitized, I felt like Dorothy waking up in Oz. A very nearby Oz. There were no talking trees in this land, no lollipop guilds. Just people who looked like you and me, doing stuff that you and I do, in front of buildings or roads that looked familiar and, in many cases, were. Old World: Color.

Pulling the little Kodachromes out of their slide boxes, I realized how thoroughly the gray shades that, for me, defined America before the late 1950s had, like a theatre scrim, distanced me from the experience of everyday lives lived before my own. Each black and white picture, I realized, reminds you that it is a document — not the thing itself. It pronounces its own pastness before you’ve even made it present. Laid out on the light table, glowing as bright as the room around them, the color slides quickly sucked me into an opposite fallacy: thinking that I was closer to the places pictured within them than I could ever be. “The day in its color,” to quote the poet Wallace Stevens, had come to seem the world itself.

So over the rainbow I went. As time allowed (and thanks to support from Chicago’s Graham Foundation for the Visual Arts) I followed Cushman’s path where I could, packing stacks of images with me as I traveled, trying to locate a country lane or a city street where he had stood, hoping to understand what had changed in that place, and why.

At times, the sites slapped me in the face — the scene before me could have been set a moment after Cushman’s own shutter snapped closed, sixty years earlier. Other efforts felt as futile as trying to reach the end of the rainbow. Absent any remaining landmarks, lost in some parking lot or farm field, I retreated to the nearest library — continuing past the clothbound volumes of Life, this time — to consult a city directory or fire insurance map that might reveal where he’d been. Back outside, I’d see it. A-ha! There’s the tree, now grown tall. There’s the foundation of the house, now laid low.

But there’s one thing I never see when I stand in Charles Cushman’s shoes: Charles Cushman. In The Day in Its Color, I said I’d aim for depth of field: I’d focus on the changing American landscape; as well as on the medium — Kodachrome film — that captured and preserved a certain view of that landscape; and finally on the man who stood, unseen, behind the camera, selecting perfect views that would soon disappear into a box, not to be seen until more than twenty years after his death. It was the third subject that proved hardest to keep in focus. Who was this man of few words and many pictures?

This summer, as my family and I head from our home in Indiana west to California, we will follow Charles Cushman along some of his routes. I’ll send back images — like those I’ve posted on this page — that highlight changes and continuities between the world that Cushman encountered and the one we find in its place. And while you’re experiencing the odd time slippage that comes from seeing dead people in living color, I’ll be stalking less visible quarry. Will I catch a glimpse of his shadow intruding into the corner of my picture frame? Could I see some unexpected detail that causes me to understand what motivated his thirty-year quest? Might I meet someone who says, “Sure, I remember Charles Cushman. Matter of fact, he got me into a pretty tight spot once”?

Eric Sandweiss is Carmony Professor of History at Indiana University. He is the author of The Day in Its Color: Charles Cushman’s Photographic Journey Through a Vanishing America, co-author of Eadweard Muybridge and the Photographic Panorama of San Francisco (winner of Western History Association’s Kerr prize for best illustrated book), and author of St. Louis: The Evolution of an American Urban Landscape.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art & architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

[…] Traveling Cushman’s route west in the past week, I am struck both by how full and how fragmented our view of the American roadscape has become. Route 66 exists so completely in our literary memories, our imaginations, our online search options, that even the faintest of efforts can serve to satisfy the curiosity that took a man of his generation many years to settle. As with every other aspect of our networked world, such access cuts both ways. While access to information democratizes our ability to fashion a coherent picture of the landscape, it furthers the atomization of our social and spatial selves. Locked in our homes, we open Google Maps for a 360-degree view of any square foot of the highway. On our GPS devices and our Mapquest searches, we break down the full experience of travel into a million randomly ranked impressions; “continue west 734.5 miles” takes up less space in our brains than “south 37 feet to unmarked intersection, take a soft right onto eastbound access road.” We know everything and we know nothing about the spaces through which we move. El Vado Motel, Central Ave. (US Highway 66), Albuquerque, NM. Photos by Eric Sandweiss. Today’s Route 66 is broken into pieces and symbols, shorn of its practical functions even as it is elevated in its “imageability.” To an extent I have to blame not just Steinbeck but Charles Cushman and the millions like him — men and women who accepted the challenge that car companies, chambers of commerce, and camera manufacturers across America laid before them. “See the USA” and appreciate the road — as I am on my own drive this month — not for what it enables us to accomplish as a society, but for what it allows us to experience as individuals. Eric Sandweiss is Carmony Professor of History at Indiana University. He is the author of The Day in Its Color: Charles Cushman’s Photographic Journey Through a Vanishing America, co-author of Eadweard Muybridge and the Photographic Panorama of San Francisco (winner of Western History Association’s Kerr prize for best illustrated book), and author of St. Louis: The Evolution of an American Urban Landscape. Read his previous blog post “Charles Cushman and the discovery of Old World color.” […]

[…] talk at Left Bank Books in Saint Louis, MO on June 21 at 7:00 p.m. Read his previous blog posts “Charles Cushman and the discovery of Old World color” and “Bits and Pieces of the Mother […]

[…] and author of St. Louis: The Evolution of an American Urban Landscape. Read his previous blog posts “Charles Cushman and the discovery of Old World color,” “Bits and Pieces of the Mother Road,” and “Kodachrome […]