By Brian Nelson

Émile Zola’s main achievement was his twenty-volume novel cycle, Les Rougon-Macquart (1871–1893). The fortunes of a family, the Rougon-Macquart, are followed over several decades. The various family members spread throughout all levels of society, and through their lives Zola examines methodically the social, sexual, and moral landscape of the late nineteenth century.

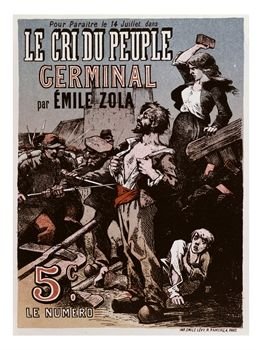

But Zola’s work contains many contradictory strains. The bête noire of the bourgeoisie believed in the traditional bourgeois virtues of self-discipline, hard work and moderation. His great working-class novels, L’Assommoir (1877) and Germinal (1885), create a sense of tragic pathos in their portrayal of the lives of the poor; but the power of mass working-class movements aroused in him an equivocal mixture of sympathy and unease. Similarly, in his treatment of sex and marriage, Zola broke the mould of Victorian moral cant; on the other hand, he admired the bourgeois family ideal.

Zola is famous for his descriptions of the material world. These descriptions are informed by vast amounts of first-hand observation and research – in the great markets of Paris, Les Halles (The Belly of Paris, 1873), the slums (L’Assommoir), the department stores (The Ladies’ Paradise, 1883), the coal fields (Germinal), the railways (The Beast in Man, 1890), etc. Zola combines the approach of a reporter with the vision of a painter in his observation of particular milieus and modes of life. His fiction acquires its power, however, not so much from its ethnographic richness as from its imaginative qualities. The observed reality of the world is the foundation for a poetic vision.

Emblematic features of contemporary life — the market, the machine, the tenement building, the laundry, the mine, the apartment house, the department store, the stock exchange, the city itself — are used as giant symbols of the society of his day. Zola sees allegories of contemporary life everywhere. In The Ladies’ Paradise, the department store is emblematic of the new dream world of consumer culture and of the changes in sexual attitudes and class relations taking place at the time. Through the play of imagery and metaphor Zola magnifies the material world, giving it a hyperbolic, hallucinatory quality. We think of Saccard, the protagonist of The Kill, swimming in a sea of gold coins, an image that aptly evokes his activities as a speculator; the fantastic visions of food in The Belly of Paris; the still in L’Assommoir, oozing with poisonous alcohol; Nana’s mansion, like a vast vagina, swallowing up men and their fortunes; the devouring pithead in Germinal, lit by strange fires, rising spectrally out of the darkness. Reality is transfigured into a theatre of archetypal forces. Human conduct for Zola is determined by heredity and environment, which pursue his characters as relentlessly as the forces of fate in an ancient tragedy.

Zola opened the novel up to entirely new areas of representation. The naturalist emphasis on integrity of representation entailed a new explicitness in the depiction of sexuality and the body. More interesting, however, is the ways in which Zola’s social and sexual themes intersect. In his sexual themes he ironically subverts the notion that the social supremacy of the bourgeoisie is a natural rather than a cultural phenomenon. The more searchingly he investigated the theme of middle-class adultery, the more he threatened to uncover the fragility and arbitrariness of the whole bourgeois social order. In Pot Luck (1882) he lifted the lid on the realities of bourgeois mores, exposing the hypocrisy of the dominant class. The bourgeois go to extreme lengths to maintain the segregation between themselves and the lower classes, whom they insistently portray as dirty, immoral, promiscuous, stupid — at best a lesser type of human, at worst some kind of wild beast. But class difference is shown to be merely a matter of money and power, tenuously holding down the raging forces of sexuality and corruption beneath the surface. We are left with a kind of stew, a melting-pot, a world where there are no clear boundaries at all.

Zola broke taboos. He was a public writer. It was entirely appropriate that, in 1898, he crowned his literary career with a political act: ‘J’accuse…!’, his famous open letter to the President of the Republic in defence of Alfred Dreyfus, the Jewish army officer falsely accused of spying for Germany. Zola’s courageous stand in the Affair showed the public writer at his best. Squarely in the tradition of Voltaire and Victor Hugo, it anticipated the work of writers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus in the twentieth century.

Brian Nelson is Emeritus Professor of French and Head of the Department of Romance Languages, Monash University, Melbourne. He has translated and edited a number of Zola novels for Oxford World’s Classics, most recently The Fortune of the Rougons.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Advertisement announcing the publication of Germinal in the newspaper Le Cri du Peuple in 1885 [public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.