The Sunday Times Oxford Literary Festival 2013 is in full swing, welcoming thinkers and writers from across the globe to our wonderful city of Oxford. We’re delighted to have over thirty Oxford University Press authors participating in the Festival this year! OUPblog will be bringing you a selection of blog posts from these authors so that even if you can’t join us in Oxford this year, you won’t miss out on all the action. Don’t forget you can also follow @oxfordlitfest and check the event schedule here.

Patricia Fara will be appearing at the Oxford Literary Festival on Thursday 21 March 2013 at 2 p.m. to discuss Erasmus Darwin and sex, science, and serendipity.

By Patricia Fara

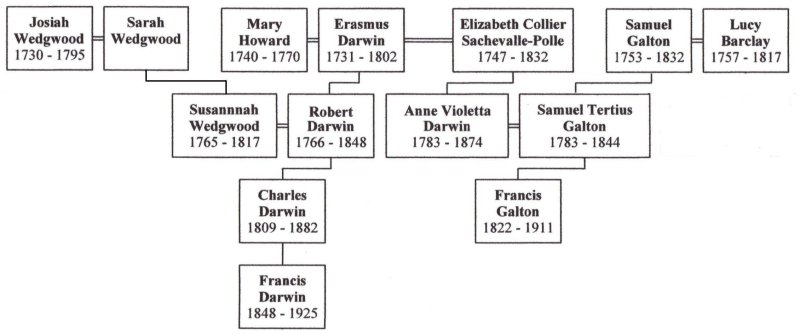

The world, wrote Darwin, resembles ‘one great slaughter-house, one universal scene of rapacity and injustice.’ Unexpectedly, that fine image of competitive natural selection was created not by Charles Darwin (1809-1882), but by his grandfather Erasmus (1731-1802). Although Charles publicly dissociated himself from this embarrassing relative, he inherited his views on abolition and evolution.

Unfamiliar now, Erasmus Darwin was well-known among his contemporaries, highly respected by many but reviled by others. Energetic and sociable, this corpulent tee-totaller was, as Samuel Taylor Coleridge put it, ‘the most inventive of philosophical men…He thinks in a new train on every subject’. On top of running a successful medical practice, Darwin was a Fellow of the Royal Society, promoted industrial innovation in the Midlands, campaigned against slavery, and was renowned for his long poems on plants, technology and evolution. The father of twelve children by two wives and his son’s governess, he envisaged an ever-changing universe that was fuelled by sexual energy and governed by natural laws rather than by God.

After his death, Darwin’s reputation plummeted because of his unorthodox ideas, but he has recently been rescued and celebrated as a prescient inventor, a key influence on Romantic literature, a champion of women’s education and the grandfather of evolution.

Darwin also became a target of political abuse. As he grew older, his opinions grew increasingly radical. Six months after the French Revolution, he exclaimed to the steam engineer James Watt, ‘Do you not congratulate your grandchildren on the dawn of universal liberty? I feel myself becoming all French both in chemistry and politics.’ In one of his long poems, The Economy of Vegetation, he welcomed the American and French Revolutions and railed against slavery.

Establishment politicians savaged him in a satirical poem called ‘The Loves of the Triangles’, which is usually seen as a light-hearted spoof of his The Loves of the Plants. But when I took the trouble to read it carefully, I realized it was far more substantial. Terrified by threats to their comfortable life style, these political poets exaggerated the risk of the French Revolution creeping across the Channel. And in particular, they focussed on Zoonomia, Darwin’s hefty medical treatise.

Although a strong influence on grandson Charles, Zoonomia was deemed so subversive that it was put on the Vatican’s banned list. Towards the end of this book, Darwin dared for the first time to suggest in print that the Bible was not literally true – that the universe was created much longer than 6000 years ago. Still worse, he proposed that human beings have gradually evolved over the millennia from primitive organisms. Or as he put it, ‘in the great length of time, since the earth began to exist…warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament…possessing the faculty of continuing to improve by its own inherent activity, and of delivering down those improvements by generation to its posterity…’

Parodists fantasised about vegetables growing wings, algae turning into fish, and people rubbing off their tails by sitting in caves. Facile jokes, perhaps, but evolution implied that the working classes might better themselves and gain positions of power. Scared off by the adverse publicity, Darwin retreated to finish his most contentious work, The Temple of Nature, which was published the year after he died. This manifesto for progressive evolution revealed him to be a materialist who believed not only that God has played no role in the continuous development of the universe, but also – still more controversially – that life stemmed from matter rather than from a divine spark. Living organisms, Darwin explained, first appeared deep in the ocean. Through successive generations, these minute beings gradually grew larger, acquiring new forms and functions until whales governed the seas, lions the land, and eagles the air – and the entire process culminated in the appearance of human beings.

Modern readers often find Erasmus Darwin’s poetry excruciating, but it was very popular at the end of the eighteenth century. Since his contemporaries took him seriously, then so too should historians. Committed to progress in every field – scientific, technological, social, biological – Darwin was a champion of Enlightenment thought who provided vital inspiration for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. A controversial political radical, he campaigned for abolition and female education, and challenged Christian orthodoxy by publishing a theory of evolution before his celebrated grandson was even born.

After spending several years with Erasmus Darwin, I know that I will never like his poetry. On the other hand, I have come to admire him enormously for his determination to make the world a better place. That may sound hackneyed, but what better aim in life could anyone have?

Patricia Fara is the Senior Tutor of Clare College, Cambridge, and she specializes in eighteenth-century history of science. Prize-winning author of Science: A Four Thousand Year History (Oxford University Press, 2009), her latest book is Erasmus Darwin: Sex, Science and Serendipity (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Darwin family tree by Carol Christiansen. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

I never knew during he was also to struggle with the political movement. I strongly believe, political and religious movements have hurt progress of science through globe.

[…] this point Moseley teamed up with Charles Darwin, the grandson of the Darwin, and produced a paper based on a detailed study of how X-rays behaved when reflected by metal […]