By Travis McDade

On a “60 Minutes” episode on Sunday 28 October, Bob Simon looked at the Barry Landau archives theft case. Aside from some official-sounding but unsupportable claims (“Barry Landau carried out the largest theft of these treasures in American history”) it was a pretty good show. Still, one part rankled.

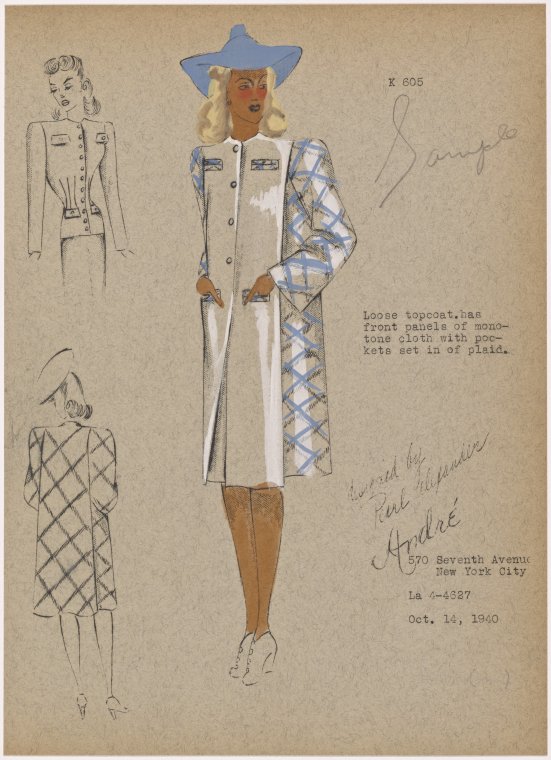

In the middle of the segment, Simon was shown several coats Landau had outfitted with special pockets in which he could secret documents before leaving victim institutions. Everyone on camera seemed alternately baffled or impressed by the gee-whiz ingenuity of the things. It played very much as if jackets with deep pockets were some sort of demonstration of the lengths to which criminals will go instead of what they actually are: a theft technique so old and hackneyed that if there was a class called Library-and-Archives-Thief 101, it would be covered in the first hour. Sewing trick pockets into coats is, quite simply, as old as coats.

Witness the 1893 tale told by Melvil Dewey. He recounted to a crowd the story of a library thief who was caught because the inside of his coat was so weighed down with books it did not flap in the Chicago wind — a fact noticed by a watchful guard. A year earlier, the Pratt Institute Free Library recorded in the Library Journal its first run-in with a thief, a young man who would secret books into a “pocket he had specially made for the purpose.” This was the sort of thing Publisher’s Circular was referring to, in 1907, when it warned of a coat’s “hare pocket.” A quarter century earlier, an article in The American Bookmaker told subscribers to “Look out for the bibliokleptomaniac…. While pretending to be looking over the new books he contrives to slip one into an inside pocket.”

But it was not just pockets; men’s coats were the Swiss Army knife of book theft, a fact noted in William Roberts’ 1895 The book-hunter in London. A coat whose lining had been ripped out would allow a thief to reach through from the inside and grab what he was looking for. A coat folded over an arm was a great screen for a nimble thief to disguise his light fingers. There was almost no end to the use of a correctly outfitted garment including, presumably, protection from the elements. Fully understanding the danger these things presented, Adolph Growoll gave, in an 1890s practical guide to American bookmen, this advice: “strangers with cloaks or loose coats with capacious pockets should be closely watched.”

In every decade of the 20th century, and each of the first two of this one, some man has used his coat to steal valuable documents, maps, and books. It is the hardy perennial of cultural heritage theft. And that is why it was so galling to see Barry Landau’s togs treated as some sort of next-level adaptation that made his thefts impossible to anticipate, or foil. In truth, Landau was no savant. He was as typical and mundane as these sorts of thieves get, and the only thing about his coats that should attract attention is how sad it is they managed to serve him so well.

Just imagine, for instance, a world where people had been, for decades, stealing cars with the same tool, again and again. Imagine that, despite this, few car manufactures, car owners, and members of law enforcement took any steps to adapt to the practice, nor even recognize its existence. Imagine them, in a 2012 news magazine segment, smiling and shaking their heads with wonder at the ingenuity of this particular tool. In reality, car manufacturers routinely design features that make their products harder to steal, owners take common sense — even outlandish — steps to keep their cars safe and law enforcement adapts to the changing circumstances. But of course they do. Cars are important.

Travis McDade is Curator of Law Rare Books at the University of Illinois College of Law. He is the author of the upcoming Thieves of Book Row: New York’s Most Notorious Rare Book Ring and the Man Who Stopped It and The Book Thief: The True Crimes of Daniel Spiegelman. He teaches a class called “Rare Books, Crime & Punishment.” Read his previous blog posts: “Barry Landau and the grim decade of archives theft” and “The difficulty of insider book theft.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

Image credits: Headline image via spxChrome, iStockphoto.

[…] professionalization of library theft permalink buy now read more Posted on Thursday, April 4th, 2013 at 8:30 am […]