By Gill Bennett

On Friday, 13 July 1962, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan sacked a third of his Cabinet. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Lord Chancellor, the Ministers of Education, Defence, Housing and Local Government, and the Ministers for Scotland and without Portfolio all lost their jobs in an episode that became known as the ‘Night of the Long Knives’. This dramatic phrase, most frequently used to describe Hitler’s bloody purge at the end of June 1934 of the leadership of the Sturmabteilung (his paramilitary Brownshirts), has since become political shorthand for any ruthless political manoeuvres and unexpectedly brutal reshuffles. Macmillan’s ministerial victims in July 1962 certainly considered his actions both ruthless and brutal. As the Liberal MP, Jeremy Thorpe, memorably put it: “Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his friends for his life.”

During 1962 Macmillan had become increasingly frustrated by what he saw as the inability of his colleagues (particularly the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Selwyn Lloyd) to embrace the strategies he considered essential to restore the government’s fortunes at a time when both the economic and industrial outlook in Britain was troubled. The Conservative government, in power since 1955 under Eden and then Macmillan, was doing badly in the polls and in the spring of 1962 had some disastrous by-election results. The Party was divided on issues such as Britain’s application to the Common Market and the future of Northern Rhodesia. Ministers squabbled between themselves over defence and the economy. The Chancellor’s spring Budget — increasing taxes on sweets, soft drinks and ice cream and so denounced as a ‘kiddy tax’ — was a public relations disaster. But in the view of Lloyd and others, Macmillan’s proposals for a new approach based on an incomes policy went against the principles of prudent economy and Conservatism itself. Something had to give.

On the overseas front, things looked grim too. Relations with the United States were strained over nuclear policy and other issues. There were tensions with the Commonwealth about Britain’s application to the EEC, while negotiations with Brussels were deadlocked and De Gaulle working up to his first veto. In Laos, a renewed outbreak of civil war raised the spectre of Western intervention and the Central African Federation was breaking up. East-West tension, to reach its apogee a few months later in the Cuban missile crisis, was running high. As Macmillan later commented, while he accepted in principle Cowper’s line that “Variety is the spice of life,” he “sometimes felt that the flavouring could be a little overdone.”

Encouraged by his Home Secretary and long-standing rival, R.A. (Rab) Butler, the Prime Minister decided that the Chancellor of the Exchequer must go. But how did a change at the Treasury turn into a ministerial massacre? After the event, Macmillan claimed he was rushed into the sackings on 13 July by a mixture of political conspiracies against him and press speculation. The precise timing of his move certainly owed much to the stories that appeared in the press on 12 and 13 July, fuelled by Butler’s remarks to press baron Lord Rothermere at lunch on the 11th. But it is clear that the Prime Minister had had a major reshuffle in mind for some time. Indeed, as he complained afterwards when lambasted by the media, he had been urged by the press to sack ineffective ministers, then criticized for doing so. Macmillan, a very old and wily political hand, was not overly surprised at this contradiction. Meanwhile, he noted in his diary that there were “altogether 10 new faced in the administration” and a “sense of freshness and interest” in Cabinet.

It has often been said that Macmillan did most harm to his own reputation by the Night of the Long Knives, but there is surely an element of hindsight here. Things certainly got worse for his government at home and abroad; he was unable to carry through many of the policy changes he sought; and he was to resign as Prime Minister in October 1963, succeeded by Sir Alec Douglas-Home. In his memoirs, published in 1973, Macmillan claimed he had made a ‘serious error’ in July 1962 in combining the sacking of the Chancellor — which was inevitable — with a general reconstruction of his government. At the time, however, the evidence suggests he knew exactly what he was doing. Certainly he regretted it, in that he hated the personal element of the purge; telling old friends and colleagues they no longer had a job was undoubtedly painful. But in political terms he (and Butler, whose role in the episode is hardly benign) had been clear it was both necessary and desirable, even if events prevented the purgative from having the full effect he intended.

“At a time like this,” Macmillan had written in his diary on 18 June 1962, “we should follow Danton’s famous words” in his address to the revolutionary French Legislative Assembly in 1792: “Il faut de l’audace, encore de l’audace, toujours de l’audace.” And despite Macmillan’s famously languid patrician style, he was a politician who did not lack boldness when he thought it necessary. “Great national troubles, even disasters,” he wrote, “can be faced with calm and equanimity by Ministers of courage.” 13 July 1962 may not be an anniversary that the Conservative Party can look back on with pride, but nor is it correct to see it, as Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell did, merely as “the act of a desperate man in a desperate situation.” The execution was certainly clumsy, but Macmillan wasn’t the only one who thought the blow should fall. As Rab Butler told Press Secretary Harold Evans, “I do understand the Prime Minister’s motives and I am behind him…. But it wasn’t done properly.”

Macmillan’s actions on 13 July 1962 were the equivalent of putting his ministerial Scrabble letters back into the bag in the hope of getting a more useful set. In Macmillan’s view, drastic action was clearly needed to reverse the downward trend. But his colleagues had responded negatively to his proposals for a new approach and reform of the labour market. They did not share his feeling, as he later expressed in his memoirs, “that we were moving into a new situation where, as in the Einstein world, cause and effect seemed to follow different rules.” (An American journalist, visiting Britain in June 1962, put it more prosaically: Conservatives, he said, “don’t really smile.”) In that case, Macmillan seems to have decided, they should be given something to cry about.

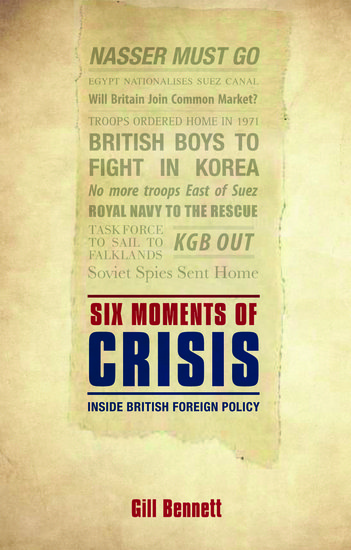

Gill Bennett, MA, OBE was Chief Historian of the Foreign & Commonwealth Office from 1995-2005 and Senior Editor of the UK’s official history of British foreign policy, Documents on British Policy Overseas. She is the author of the upcoming book Six Moments of Crisis: Inside British Foreign Policy. As a historian working in government for over thirty years, she offered historical advice to twelve Foreign Secretaries under six Prime Ministers. A specialist in the history of secret intelligence, she was part of the research team working on the official history of the Secret Intelligence Service, written by Professor Keith Jeffery and published in 2010. She is now involved in a range of research, writing and training projects for various government departments.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles about British history on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

Recent Comments

There are currently no comments.