By Russell Goulbourne

Thursday 28 June 2012 marks the tercentenary of the birth of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, one of the most important and influential philosophers of the European Enlightenment. The anniversary is being marked by a whole host of commemorative events, including an international conference at my own institution, the University of Leeds, which begins today. Rousseau arouses this kind of interest because his theories of the social contract, inequality, liberty, democracy, and education have an undeniably enduring significance and relevance. He is also remembered as a profoundly self-conscious thinker, author of the autobiographical Confessions and Reveries of the Solitary Walker.

Rousseau started writing his Confessions in 1764. He begins at the beginning: his birth, three hundred years ago today. His was not an auspicious entry into the world: “I was born almost dying; they despaired of saving me.” Little more a week after he was born, his mother, aged thirty-nine, died of puerperal fever: “I cost my mother her life, and my birth was the first of my misfortunes.” Rousseau felt that he had killed his mother, and this burden of guilt remained with him throughout his life. As a result, motherhood took on, for him, a quasi-sacred quality. In a letter of 22 July 1764 he warned the twenty-something marquis de Saint-Brisson that “a son who quarrels with his mother is always wrong” because “the right of mothers is the most sacred I know, and in no circumstances can it be violated without crime.” Two years earlier, in Emile, which Rousseau seems to have considered his most important work, he underlined what he saw as the crucial role mothers had in educating their children, going so far as to champion breastfeeding as the bedrock of sound society: “Let mothers deign to nurse their children, morals will reform themselves, nature’s sentiments will be awakened in every heart, the state will be re-peopled.”

Rousseau’s origins remained with him in another way too, as the opening of the Confessions also suggests: “I was born in 1712 in Geneva, the son of Isaac Rousseau and Suzanne Bernard, citizens.” Geneva at that time had three orders of citizens; the watchmaker Isaac Rousseau was one of the full citizens, who made up less than a tenth of the city’s population. As his father’s son, Jean-Jacques was immensely proud of that citizenship. While his contemporaries Voltaire and Diderot repeatedly tried in different ways to conceal their identity, for instance by publishing controversial works under the veil of anonymity, Rousseau, by contrast, followed a policy of openness and self-exposure. So, for instance, the first edition of the Social Contract, published by Marc-Michel Rey in Amsterdam in 1762, displays on the title page the name ‘Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Citizen of Geneva’. At a time of strict censorship, the proudly Genevan Rousseau embraced his public role as an author and what he published became a crucial part of his identity.

By the end of his life, however, we find Rousseau turning inwards. He begins his last work, the Reveries, by insisting that he is writing for himself alone, his aim being to acquire self-knowledge: “Alone for the rest of my life, since it is only in myself that I find solace, hope, and peace, it is now my duty and my desire to be concerned solely with myself. It is in this state of mind that I resume the painstaking and sincere self-examination that I formerly called my Confessions. I am devoting my last days to studying myself and to preparing the account of myself which I shall soon have to render.” Rousseau started writing the Reveries in September 1776; they were left unfinished when he died at Ermenonville on 2 July 1778, four days after his 66th birthday.

By the end of his life, however, we find Rousseau turning inwards. He begins his last work, the Reveries, by insisting that he is writing for himself alone, his aim being to acquire self-knowledge: “Alone for the rest of my life, since it is only in myself that I find solace, hope, and peace, it is now my duty and my desire to be concerned solely with myself. It is in this state of mind that I resume the painstaking and sincere self-examination that I formerly called my Confessions. I am devoting my last days to studying myself and to preparing the account of myself which I shall soon have to render.” Rousseau started writing the Reveries in September 1776; they were left unfinished when he died at Ermenonville on 2 July 1778, four days after his 66th birthday.

Rousseau had been staying at Ermenonville, some fifty kilometres north-east of Paris, as the guest of his pupil and friend the marquis de Girardin. He was buried on the little island known as the Isle of Poplars in the middle of the ornamental lake in the grounds of Girardin’s château. In October 1794, with great pomp and ceremony, his remains were transferred to the Panthéon in the centre of Paris. But his empty tomb remains on the island, although Girardin’s château is now a plush hotel. Two years after Rousseau’s death, Girardin replaced the temporary tomb with an elaborate one in the form of a Roman altar, designed by the painter Hubert Robert. Fittingly, on one side of it, a bas-relief by the sculptor Jacques-Philippe Lesueur shows a mother nursing her infant while reading Emile.

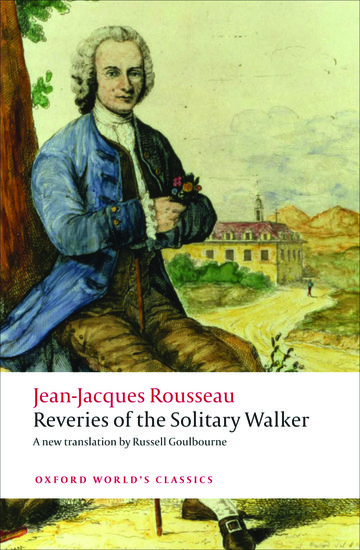

Russell Goulbourne is Professor of Early Modern French Literature at the University of Leeds. He has translated Diderot’s The Nun and Rousseau’s Reveries of the Solitary Walker for Oxford World Classics.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

[…] Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Émile of 1762 pleaded for a reform of education, a “natural” education without drill. Rousseau’s plea for the careful observation of children initiated the keeping of diaries by parents and teachers. Philosopher Dietrich Tiedemann was the first to publish a diary, in 1787. It follows his son’s development during the 30 months since his birth and includes a number of observations on Friedrich’s acquisition of speech. More diaries followed during the 19th century, but diary studies became a real boom after Darwin (1877) published his own observations on son William’s early development. Studies of language acquisition, for a variety of languages, kept appearing till the present day. They became an important database for theories of language acquisition. […]