By Lydia Carr

The path of the biographer is littered with terrors. Few, to be fair, match the risks listed on the fieldwork forms put out by various Institutes of Archaeology, those exhaustive documents intended to pinpoint every potential danger (and indemnify the sponsoring department against paying for more than a reasonable number of snakebite treatments). But as I’ve often said, biographic research, at least regarding twentieth-century subjects, resembles nothing as much as the first five minutes of a Doctor Who episode, or the last five pages of a M.R. James story. You know the type of thing; the lonely academic (writer, archaeologist, explorer) in a dim library (cave, alien spaceship, church) looking over the crabbed and dusty manuscript (letters, runic inscription, half-ruined tomb), unaware that all the time the creepy unknown is just… about… to… pounce!

And then the Doctor comes upon the mangled remains of my corpse, says “Oh no. Not — THEM!” or words to that effect, and you get the theme music.

The research for Tessa Verney Wheeler: Women and Archaeology Before World War II, was fairly typical of the process. My subject was primarily active between 1922 and 1936 (when she died), and along with her husband Mortimer Wheeler excavated several extraordinarily interesting Roman and prehistoric archaeological sites in England and Wales. Being of a sanguine temper, I evolved a simple research methodology of showing up at the various museums associated with those sites, asking politely for the Verney Wheeler materials. Then, when I received my inevitable initial answer (always very nicely) that they were sorry to say there was nothing relating to Verney Wheeler in stock, I even more politely asked if I could just have a personal look for them. And just as inevitably, I would poke and prod through dusty wine boxes and disintegrating milk crates, until I came upon a cache of letters and notebooks in Verney Wheeler’s neat, distinctive hand. Because there always was something of Verney Wheeler’s there. Cataloguers had either not been interested enough to note material, or had filed it under Mortimer Wheeler instead — a fair metaphor for Verney Wheeler’s career.

Time at the National Museum of Wales morphed from three days to two weeks, once I found the notebooks for three sites (including the Caerleon amphitheatre), a really terrific book of Wheeler-related newspaper clippings by some long-dead press service, and three years of personal and professional letters. The Somerset county archives in Taunton, allegedly uninteresting, produced a very long, very useful unpublished memoir by Wheeler henchman William Wedlake. I could only afford one trip to see it, and read frantically from the moment the doors opened to the second I was cast out into the night, as staff enthusiastically copied relevant chapters for me at top speed (with occasional references to railway timetables and encouraging shouts in my direction). The Verulamium Museum cast up, quite at random: a bill for distempering a London bathroom, a sweet letter typed by Verney Wheeler’s father-in-law, and snapshots and letters from the tent city of students who excavated the Roman town.

Actual locations were just as odd. The basement flat near Victoria, anathematized by contemporaries as dark and dingy, emerged — even in water-stained abandonment — as light and airy by modern standards (although its decaying prewar plumbing was a little scary despite that distempering). The Dorchester County Museum turned out to be keeping its archives in a deconsecrated church on the High Street, a building quite deserted apart from myself and the mice. It was another lightning trip, one week to read, copy, and remember everything related to the great 1930s excavation of Maiden Castle (barring a single afternoon off at Lyme Regis, where the shingle reflected shadowy dinosaurs). I don’t, incidentally, recommend exploring deconsecrated Dorset churches alone at dusk. If you fancy a short break from working over photographs and want to stretch your legs by checking to see what’s on the second floor, it only ensures that you discover where they are keeping the really creepy old folk costumes (the ones with the giant glass eyes and an implication of Tim Burton out of Thomas Hardy). Morris dancers are no preparation for finding those at the top of a ladder. But I did get an excellent recipe for treacle tart from the teashop around the corner, so it was probably worth the palpitations.

In writing a biography of a dead subject one is, in the end, deliberately chasing a ghost, but hopefully a benign one. The Roman temple at Lydney Park, most beautiful of all the Wheeler sites, looks over the Wye valley from its isolating hilltop, and it is the place where Verney Wheeler seemed closest at hand. I hope she is there, not in her little Roman brick tomb in St. Albans — pleasant as it is. The temple’s medicinal streams still run rusty-red with iron ore, and the entrances to the sub-Roman and prehistoric mining tunnels gape shyly behind green undergrowth. The azalea gorge that was just planted in Verney Wheeler’s day is almost tropical now, and the great trees of the park rear up over descendents of the same deer her husband drew boyishly into the corner of the excavation report’s site map. It is a fittingly remote resting place for this strange, elusive little woman, who gave so much to others while keeping her own soul hidden away.

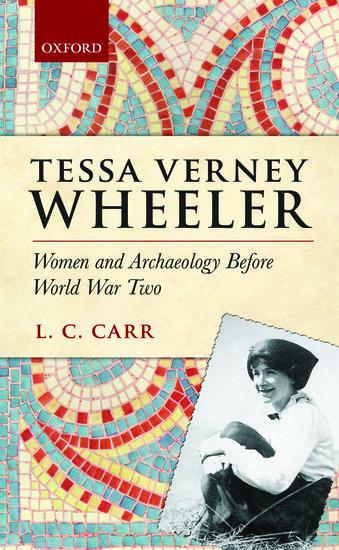

Lydia Carr was born in New York City in 1980, and took her D.Phil at Oxford in 2008. She is the author of Tessa Verney Wheeler: Women and Archaeology Before World War Two. She is currently Assistant Editor at the Chicago History Museum and in her spare time, she writes light, bright mystery novels set in the 1920s.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

[…] my last blog post, I looked at my research into the inter-war archaeologist Tessa Verney Wheeler (1898–1936) and […]

[…] of her with permission to use) but you can read about Lydia Carr’s biography of her and see more photos here. Tessa is a major figure in trowelblazing history, for her archaeological findings, her development […]

What a marvelous post — both in terms of writing and content. I encountered Tessa Wheeler in Charlotte Higgins’ excellent book, “Under Another Sky” and wanted to learn more about her. I am grateful for this fascinating read. Thank you!