By Kirk Curnutt

According to literary legend, the author of The Great Gatsby sold his soul.

Perpetually cash-strapped, F. Scott Fitzgerald spent much of his twenty-year career cranking out popular fiction for the Saturday Evening Post and other high-paying “slicks.” While Edith Wharton, Willa Cather, and William Faulkner racked up double digits in the novels column, Fitzgerald completed a paltry four and a half, with only one of them (Gatsby, of course) truly great. By contrast, he produced 160 short stories, earning a total of $241,453 off the genre – more than $3 million in today’s dollars.

These are impressive figures by anyone’s count, but critics don’t speak positively of his prolific short fiction output. Fitzgerald himself is to blame for this. In a well-known 1929 letter to Ernest Hemingway, he described himself as an “old whore” whom the Post now paid a premium “$4,000. a screw” because “she’s mastered the 40 positions [when] in her youth one was enough.” For Fitzgerald, the short story was a means to an end: it allowed him to finance his novel writing, which he considered the preeminent art form. Yet as his graphic metaphor suggests, he also resented the story market for enticing him to prostitute his talent. To command courtesan prices, he had to know how to his please his audience – and that meant recycling familiar themes, employing stock characters and scenarios, and tugging the heartstrings.

What more artistically he might have accomplished, commentators lament, had he not been so dependent on this dirty money.

Partly out of perversity and partly out of Gatsby fatigue, I’ve made it something of a personal mission as a Fitzgerald scholar to redeem his more commercial stories. I’m not talking the ubiquitously anthologized “Babylon Revisited” (1931), or “The Rich Boy” (1926), whose famous salvo of class resentment (“Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me”) is oft-cited. I’m not even talking “Winter Dreams” (1922), the best of the many stories in which Fitzgerald rehearsed Gatsby’s lost-love plot before finally writing it in 1924.

Partly out of perversity and partly out of Gatsby fatigue, I’ve made it something of a personal mission as a Fitzgerald scholar to redeem his more commercial stories. I’m not talking the ubiquitously anthologized “Babylon Revisited” (1931), or “The Rich Boy” (1926), whose famous salvo of class resentment (“Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me”) is oft-cited. I’m not even talking “Winter Dreams” (1922), the best of the many stories in which Fitzgerald rehearsed Gatsby’s lost-love plot before finally writing it in 1924.

No, I’m talking about stories with titles such as “Myra Meets His Family” (1920), “The Lees of Happiness” (1920), “Diamond Dick and the First Law of Woman” (1924), “Rags Martin-Jones and the Pr-nce of W-les” (1924), “The Unspeakable Egg” (1924), and “Love in the Night” (1925). Fitzgerald even once wrote a story called “The Love Boat” (1927). No Captain Stubing or Isaac the Bartender, but the characters definitely set a course for adventure, their minds on a new romance – they just do it in Fitzgerald’s melancholy voice, not the dulcet tones of theme-song singer Jack Jones.

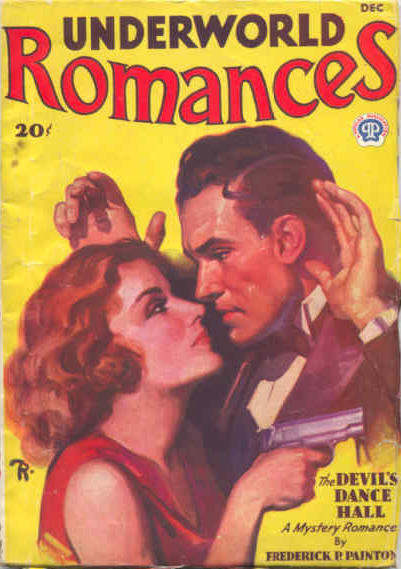

These stories aren’t neglected, I would argue, because they’re formula fiction. A great deal of 1920s’ and 1930s’ formula fiction today attracts attention. At this point, hardly a page of Black Mask Magazine, Dime Detective, Weird Tales, and Amazing Science Fiction remains unexcavated. Yet the popular genre to which Fitzgerald bears most affinity doesn’t get as much love. Nearly thirty years after Janice Radway’s influential Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Fiction (1984) helped legitimate academic study of romance fiction, exhumations of Love Story, Thrilling Love, and even period niche markets (Ranch Romances, Underworld Romances) are comparatively rare. As rare, in fact, as interest in Fitzgerald’s more sentimental excursions.

These stories aren’t neglected, I would argue, because they’re formula fiction. A great deal of 1920s’ and 1930s’ formula fiction today attracts attention. At this point, hardly a page of Black Mask Magazine, Dime Detective, Weird Tales, and Amazing Science Fiction remains unexcavated. Yet the popular genre to which Fitzgerald bears most affinity doesn’t get as much love. Nearly thirty years after Janice Radway’s influential Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Fiction (1984) helped legitimate academic study of romance fiction, exhumations of Love Story, Thrilling Love, and even period niche markets (Ranch Romances, Underworld Romances) are comparatively rare. As rare, in fact, as interest in Fitzgerald’s more sentimental excursions.

Once upon a time we would’ve attributed this indifference to sexism – and certainly we continue to struggle against the prejudice that any entertainment aimed at women lacks the gravitas of, say, gumshoes with guns. There is also a sense that romance writing lacks the deliciously subversive impulses of noir and sci-fi, a presumption that itself reflects gender bias and doesn’t really hold true upon close inspection. But I also think the guilt lies with a broader culprit. I think it reflects an uncertainty about how to quantify descriptions of romantic desire – not necessarily sexual desire, but that big abstraction, love. How exactly do we separate “genuinely” affecting descriptions of it from the sappy and hokey?

Once upon a time we would’ve attributed this indifference to sexism – and certainly we continue to struggle against the prejudice that any entertainment aimed at women lacks the gravitas of, say, gumshoes with guns. There is also a sense that romance writing lacks the deliciously subversive impulses of noir and sci-fi, a presumption that itself reflects gender bias and doesn’t really hold true upon close inspection. But I also think the guilt lies with a broader culprit. I think it reflects an uncertainty about how to quantify descriptions of romantic desire – not necessarily sexual desire, but that big abstraction, love. How exactly do we separate “genuinely” affecting descriptions of it from the sappy and hokey?

Allow me an analogy to illustrate. I spent most of 2009-2010 writing a book about Brian Wilson, the “genius” Beach Boys composer whose pop iconicity bears more than a few parallels to the Fitz. (If Pet Sounds isn’t The Great Gatsby in five-part harmony, I don’t know what is). One ambition was a chapter on lyrics that would ask why songs such as “Surfer Girl,” “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” and the incandescent “God Only Knows” are considered so guilelessly pure in intent as to become nearly hymn-like, despite the obvious simplicity of their text. On a very basic level, I wanted to know why Wilson’s words (or his collaborators’ words, in most cases) were deemed vulnerably “sincere” when those of Paul McCartney in, say, “My Love” (1973) or (gasp) Celine Dion in “My Heart Will Go On” (1997) are derided as treacle and saccharine.

Conceptually, it seemed an interesting project, and probably less la-di-da than insisting upon the colonialist hegemony of “Everybody’s gone surfin’ / Surfin’ U.S.A.” From the start, however, I was befuddled by the lack of critical precedent. Nowhere in the wealth of inspiring writing on pop lyrics could I find an apparatus for assessing the verbal formulae of love songs. The best I could come up with was a line from the great sociomusicologist Simon Frith, who in Performing Rites: On Value in Popular Music (1996), writes that pop songs aren’t so much about the authenticity of love as about the formulas of love by which we legitimate emotions: “The question becomes, in other words, why some sorts of words are heard as real or unreal, and to understand this we have to understand that how words work in song depends not just on what is said, the verbal context, but also on how it is said – on the type of language used and its rhetorical significance; on the kind of voice in which it is spoken.”

Well, if Simon Frith couldn’t solve the problem, I wasn’t going to, and I ultimately scrapped the plan in favor of a more straightforward discussion of Wilsonian themes and motifs. (And rest assured, themes and motifs do exist in Beach Boys’ lyrics). I often feel similar frustration when trying to assess Fitzgerald’s rhetoric of romance. For example, at conferences and in classes when I read aloud the following passage from “The Love Boat” in which two strangers, Mae Purley and Bill Frothington, “lock eyes” for the first time, I inevitably excite sniggers:

“They made love. For a moment they made love as no one ever dares to do after. Their glance was closer than an embrace, more urgent than a call. There were no words for it. Had there been, and had Mae heard them, she would heave fled to the darkest corner of the ladies’ washroom and hid her face in a paper towel.”

On the other hand, I can recite a passage from The Great Gatsby that will make grown men weep: “Out of the corner of his eye Gatsby saw that the blocks of the sidewalks really formed a ladder and mounted to a secret place above the trees—he could climb to it, if he climbed alone, and once there he could suck the pap of life, gulp down the incomparable milk of wonder”—the famous passage, in other words, that culminates with Gatsby’s desire for Daisy Buchanan described as a “tuning fork … struck upon a star.”

What makes the former seem overripe while the latter is regarded as one of the most beautiful moments in American literature?

I wish I knew.

I’m tempted to say it’s because one appears in a commercial short story dopey enough to go by the title “The Love Boat” and that the other—well, the other comes from The Great Friggin’ Gatsby.

Ultimately, however, I think we lack an extensive enough knowledge of “the type of language used” in 1920s’ love stories to judge beyond that flippant response. Attaining that knowledge would require us to break down that arbitrary dividing line that separates “literary” expressions of love from popular ones—a dividing line that, again, has exiled many Fitzgerald short stories from “serious” consideration for way too long.

Such a study wouldn’t have to be hard. I envision a broad, encompassing book not unlike Stephen Kern’s The Culture of Love: Victorians to Moderns (1992). This highly regarded analysis does indeed categorize “the type[s] of language used” and “the kind[s] of voice in which [those types are] spoken” in descriptions of various romantic gestures (first glances, kissing, coitus itself) appearing in authors as diverse as John Ruskin, George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, D. H. Lawrence, and Virginia Woolf. A similar effort would simply set Fitzgerald alongside examples from pulp romances, competing authors of Post love stories, and the racier fare that distinguished its romance tales with “spicy” in the title (Spicy Stories, Spicy Adventure Stories, etc).

Such a study wouldn’t have to be hard. I envision a broad, encompassing book not unlike Stephen Kern’s The Culture of Love: Victorians to Moderns (1992). This highly regarded analysis does indeed categorize “the type[s] of language used” and “the kind[s] of voice in which [those types are] spoken” in descriptions of various romantic gestures (first glances, kissing, coitus itself) appearing in authors as diverse as John Ruskin, George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, D. H. Lawrence, and Virginia Woolf. A similar effort would simply set Fitzgerald alongside examples from pulp romances, competing authors of Post love stories, and the racier fare that distinguished its romance tales with “spicy” in the title (Spicy Stories, Spicy Adventure Stories, etc).

Until somebody undertakes such a massive, revisionary task, I fear Fitzgerald’s more formulaic “love songs” will fall on the deaf ears. Within the history of the American short story, the author himself will remain the master of the “40 positions,” and we will continue to cite 241,453 excuses not to read him any differently.

Kirk Curnutt is professor and chair of English at Troy University’s Montgomery, Alabama, campus, where Scott Fitzgerald met Zelda Sayre in 1918. His publications include A Historical Guide to F. Scott Fitzgerald (2004), the novels Breathing Out the Ghost (2008) and Dixie Noir (2009), and Brian Wilson (2012). He is currently at work on a reader’s guide to Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

Very inspiring. Great work Kirk Curnutt.

I think “Tender Is the Night” is greater than “Gatsby.” Nice article.

[…] OUPblog details F. Scott Fitzgerald's many years writing popular fiction for the Saturday Evening Post and other high-paying magazines, which financed his career as a […]

[…] Seeking redemption for Fitzgerald’s short stories. […]

[…] lovers who can’t quite get together meet in the same city where Zelda spent her last years. F. Scott Fitzgerald has clearly been a strong influence on Gwendoline Riley’s writing and Joshua Spassky achieves […]

[…] openness and something intrinsically joyful and forward-looking. The Astaires in fact exemplified F. Scott Fitzgerald’s fundamentally romantic if elegiac conception of America as “a willingness of the […]