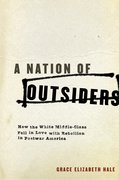

This month marked the 60th anniversary of The Catcher in the Rye, so what better way to wrap up July than by examining Holden Caulfield’s affect on the American adolescent rebel? The following is an excerpt from Grace Elizabeth Hale’s new book, A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell in Love with Rebellion in Postwar America.

After 1951, if a person wanted to be a rebel she could just read the book. Later there would be other things to read—Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice, and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. But J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye was the first best seller to imagine a striking shift in the meaning of alienation in the postwar period, a sense that something besides Europe still needed saving. The success of this book and the many other novels, autobiographies, and films that followed its pattern made the concept of adolescent alienation commonplace, but in the postwar era the very idea shocked many Americans. Adults who had lived through depression and war believed that children growing up in peace and prosperity—Life named them “the luckiest generation”—should be happy. Salinger’s antihero Holden Caulfield was a particularly unlikely rebel. He lived unconstrained by poverty, racism, or anti- Semitism, and he did not face the narrow options available for ambitious girls. Instead, Holden’s alienation was personal, psychological, and spiritual. Salinger’s novel helped create a model for the rebel of the future by popularizing the problem of middle-class adolescent alienation….

Holden Caulfield becomes a rebel that both intellectuals and young middle-class Americans can bond with and even love. These readers feel connected to Holden and sometimes in turn to other Catcher fans in a kind of pop cultural community of outsiders. The act of telling, Holden’s expression of his own alienation, helps create both a new model of the white well-off adolescent as outsider and a new kind of belonging. In this way, Catcher satisfies contradictory feelings, the urge to be self-determining through resisting social rules and conventions and the urge to be a part of a community. And despite Caulfield’s gender, this reconciliation of contradictory desires through identifying with outsiders and rebels seems to work for some female as well as male readers. A first-person narrative about a person who is neither an adult nor a child, the novel displaces the incompatibility of these desires into the borderlands of adolescence.

Like Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, published in 1884, Catcher is a radical portrayal of disillusionment with America disguised by its author as a tale of childhood adventure. Critics and scholars have remarked on the connections between the two coming-of-age novels with their white boy protagonists since soon after Catcher was published. Huck’s running away with the slave Jim is the equivalent of Holden’s screaming, “Sleep tight, ya morons! ” as he leaves Pencey Prep. Their upthrust fingers in the faces of their worlds, their attacks on what their societies most value—slave property and a secure, upper-middle-class future—in both cases, rebellion preserves the boys’ innocence and dramatizes their refusal to conform, to accept the compromises adults make with their respective societies. Each novel became a part of the popular culture of its era even as it off ered a serious comment on the limits of that culture.

In Holden, critics and reviewers found a character acutely sensitive to the conformity and spiritual numbness that modern life generates in the world imagined in the novel. One fictional character’s experience of alienation, of course, mattered little historically. Catcher became a powerful model of adolescent alienation across the postwar era because of the intersection of broad historical trends with Salinger’s skill as a writer and changes in the publishing industry. In the 1950s, the paperback revolution transformed book publishing and made novels almost as cheap as magazines. At the same time, the postwar economic boom gave white middle- class teenagers more money to spend and more leisure time in which to enjoy their purchases. Paradoxically, the novel also got a boost from journalists’ and intellectuals’ anxiety about “mass culture”; Catcher sold 1,500,000 copies in paperback in its first decade. Catcher in the Rye offered a model for rebellion against mass culture even as it was also a very profitable part of mass culture.

Though the novel predates the invention of two new popular culture genres aimed at the same white middle-class youth market, Catcher, rock and roll music, and teenpics (films made for teenagers) all shared an oppositional stance toward conventions and norms imagined as central to American life. In fact, the very idea of white middle-class adolescent alienation became increasingly powerful because older observers like journalists and white middle-class adolescent fans themselves connected their rebellion to the oppositional positions of other groups: the “plague” of juvenile delinquency among workingclass urban youth, the self-conscious rebellions of bohemians and artists, and, even more importantly, African Americans’ historic position as outsiders in America.

It also helped that the adolescents in those homes lay on their twin beds flipping the radio dial and the pages of magazines looking for something different. No one used mass culture to resist mass culture better than middle-class white teenagers. For the first time, in the postwar period, a critical mass of adolescents had the money and the leisure time to cultivate their own cultural tastes. Their parents saw this prosperity and could not understand how these kids could have any problems. Businesses like radio stations, record companies, and Hollywood saw this prosperity and thought about how to reach these new consumers. Radio and the movies, in particular, needed new markets, as television became the family entertainment of choice in the growing suburbs. As Esquire argued in 1965 in an article entitled “In the Time It Takes You to Read These Lines the American Teenager Will Have Spent $2,378.22,” “this vague no-man’s-land of adolescence” had become “a subculture rather than a transition.”

What many of these teenagers wanted was separation, something, anything to distinguish and distance them from their parents and other adults. With help from the music, movie, and radio industries, they created a new teen culture grounded in a mood of opposition to their parents and their plenty. In contrast to a more respectable emotional repression, white teenagers increasingly valued the expression of passion and desire. In place of their parents’ controlled and polished forms of entertainment, they sought the raw and frenetic. And in defiance of the white norms of middle-class America, they embraced popular black music and fantasies of African American life. For teenagers and college students, mass culture was not just a problem, as many intellectuals argued in the mid-twentieth century. It was a solution. It was not just the space of a conformity that killed American individualism. It was a space of resistance. It was not just the household of the organization man. It was the home of the rebel. Most importantly, it gave white teenagers a window, however smudged, on black cultural expression.

In the 1950s and 1960s, mass culture gave some young white Americans a glimpse of redemption. Rebels and outsiders were out there. Other possibilities existed. A novel or rock and roll song or a fi lm could be a vehicle for expressing feelings of alienation, for thinking about a different kind of life. The fact that many outsider characters were male did not stop young white women from seeking alternatives too, although rebellion was always more dangerous for them. Holden Caulfield may not have had the answers, but he suggested how some white middle-class white kids could start asking the questions.

Grace Elizabeth Hale is Associate Professor of History and American Studies at the University of Virginia.

You betcha! All of these writers deeply affected me but especially Jack Kerouac in my profoundly miserable youth. In the “noise pollution” of our world today, a contemporary voice like his would not stand out. Outsider, contrary, rebellious; how about thoughtful …now intrinsic to my heart and soul…

A few “visual” examples below. My written works; posthumously? “Oh, no, not the climate” now.”

Outsider Nature Art Photography – j. Madison Rink

http://www.outsidernatureartphotography.blogspot.com

“The Road” j. Madison Rink

http://rinkarte.com/TheRoad/TRtmnl01.html

Holden Caulfield represents complete rejection of the middle class: its values, lifestyle, everything. It’s all phony.

Now many of the baby boomers who read this book and were inspired by it to reject every value they learned from their middle class upbringing are asking “What happened to the middle class?”

The answer is simple: They rejected middle class values, lifestyle, everything. Like Holden Caulfield, they said it’s all phony.

I mean, if a lot of people reject something, it tends to disapear.